An Analysis of the Evolution of Rhetoric in American Political Debate

Written by Miles Gendebien; Edited by Andrew Ma

Published on August 28th, 2024

Former President Donald Trump (left) and President Joe Biden clash during the first presidential debate of the 2024 election season.(ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES)

The first 2024 presidential debate between Presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump reaffirmed the disenchantment of many with contemporary American politics. An oft-stated grievance of voters and pundits alike is the uncivil speech and conduct of political candidates, which may no longer be “unprecedented” but ubiquitous in our system. The bitter aftertaste of the debate provokes the question of whether common decency has been abandoned by our politicians.

But is this perception accurate? And can we assess how the behavior of political candidates has changed, not only within the past ten years but also since the first televised presidential debate took place between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon almost six and a half decades ago?

A juxtaposition of the 1960 and 2024 debates will show that not only has programmatic substance given way to political and personal invectives but also that modern candidates are disposed to hyperbolic and superficial argumentation. American debates, in short, have become arenas for discursive brawls rather than educational platforms for candidates to inform voters, a reality only truly understood by comparing contemporary candidates to those prior. Before drawing this comparison, I first sketch the historical background, the contemporary context, and a feedback loop mechanism that may be at work in our presidential debates.

Political Rhetoric and the Use of Television

Democrat Sen. John Kennedy, left and Republican Richard Nixon, right, as they debated campaign issues at a Chicago television studio on Sept. 26, 1960. Moderator Howard K. Smith is at desk in center. (AP Photo)

To begin, the proclivity of American politicians to denigrate one another and make exaggerated or misleading claims to their constituencies is not a new phenomenon. Just a decade before the Nixon-Kennedy debate, Senator Joseph McCarthy fueled the preexisting “Red Scare” into a nationwide paranoia. Anti-Communist sentiments allowed and even encouraged right-wing politicians to slander opponents in a sort of watchdog politics, to the point that “No one dared tangle with McCarthy for fear of being labeled disloyal”. The persecutorial fervor of McCarthyism finally began to break in the same way that it had reached its pitch: in front of a TV audience. At the 1954 Army-McCarthy Hearings, Joseph Welch shocked America’s conscience when he confronted the senator with the question, “have you left no decency?”.

While the power of television for ill and for good was clear by the end of the 1950s, the novelty of a nationally televised presidential debate likely impacted the candidates’ behavior. The TV screen magnified their image to the scrutiny of a public audience, and any off-putting remark could be damaging. As Don W. Kleine wrote for The Nation, “It was as if… each knew how fearful the consequences of spontaneity might be”.

The Feedback Loop of Political Rhetoric

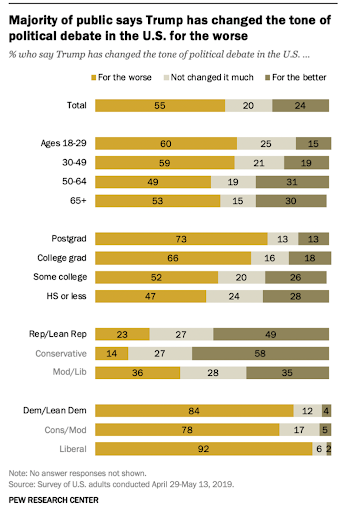

A graph depicting the results of a 2019 Pew Research Center survey regarding the impact of Trump's rhetoric on the tone of American political debate.

And what of the claim that the unprecedented nature of the past three election seasons is entirely attributable to Donald Trump and his abrasive discourse? A Pew Research Center survey found that 76% of Americans find themselves concerned with comments made by Trump despite a large discrepancy between Republicans and Democrats. Similarly, 76% of post-grads felt that Trump had changed the tone of political debate for the worse. On the other hand, the American media has become increasingly polarized as partisan and opinionated cable news hosts have replaced highly trusted broadcast journalists like Walter Cronkite who held large national followings and were seen as strictly reporting the facts. Nearly ¾ of adults believe that the news media is increasing polarization in this country, despite being part of its viewership. Not coincidentally, FOX News and MSNBC were both founded in the 1990s.

Ultimately, the harsh rhetoric indicates a change over time in how politicians present themselves to the public, a shift which may be traceable to a feedback loop connecting the American voter, political candidates, and the media. Assuming that politicians and politically biased media outlets seek positive responses from the public, the behavior of candidates and news hosts is selected almost entirely by the American audience. Americans endorse polarizing speech and intransigent behavior when they turn on their televisions or enter the voting booth, and I argue that this is due to the average American’s disinterest with factual argumentation and inclination to root for their respective “fighters.” In order to understand why political actors behave the way that they do, one must identify what characteristics the public selects for.

The Evolution of Rhetoric in Political Debate

I will now compare the 1960 and 2024 debates to ascertain why there has been such a change in the way that politicians present themselves. The findings suggest the need to conduct research into the possibility that voters’ preferences and candidates’ tactics are now in a feedback loop enabled by mass media. The assumption here is that candidates will say and do what is most likely to win them elections, and Americans signal to candidates what to say and do with their votes and viewerships.

The first obvious difference between the two debates is the amount of plausible and unambiguous facts candidates used in their arguments, as opposed to information that is vague, superficial, or unintelligible. I consider a plausible and unambiguous fact to be a piece of information given by a candidate that provides some specific quantifiable value or is otherwise evidently true and undisputed. This comes from the presumption that the more quantifiable and self-evident the information is, the more likely it is to appear true to the audience of a debate, hence the fact that an intelligent voter would generally find clarity and precision more plausible than ambiguity and incoherence. In 1960, facts were mostly given in flurries to emphasize or support well-defined arguments:

“If a Negro baby is born… he has about ½ as much chance to get through high school as a white baby. He has ⅓ as much chance to get through college as a white student. He has about a third as much chance to be a professional man. About half as much chance to own a house. He has about 4 times as much chance that he’ll be out of work in his life.”

I also consider plausible facts to be information that is not statistical but is specific and undisputed by the other candidate,

“After my trip to South America I made recommendations that a separate inter-American lending Agency be set up.”

And thirdly, a plausible fact is information that is logically or evidently true,

“The farmer produced these surpluses because the government asked him to through legislation during the war.”

But I do not include as plausible facts statements that lacked sufficient evidence, were overly vague, or evidently untrue. Consequently, these statements were not plausible enough or did not have adequate clarity to be considered informative to voters,

“Apple and all of these companies, they were bringing money back into our country”

“I’ve passed the most extensive climate change legislation in history”

President Joe Biden delivers remarks during a session on “Action on Forests and Land Use”, Tuesday, November 2, 2021, during the COP26 U.N. Climate Change Conference at the Scottish Event Campus in Glasgow, Scotland. (Official White House Photo by Adam Schultz)

In the first quotation, Trump fails to clarify who “all of these companies” are. Moreover, he fails to provide any amount of money or to specify how the unnamed companies were bringing it into the country. Of course, the implication is that many companies were bringing large quantities of money into the United States, but implicit information is not informative. The more that is implied in a statement, the less that is clarified by that statement, which serves to persuade more than to educate or inform. In the second quotation, I consider Biden to be making a claim, not providing a fact. While what he is saying may be true, it is not evidently so. He does not clarify what is meant by “the most extensive climate change legislation,” and leaves open the criteria for what makes legislation on climate change extensive. The implications of his statement may be that he has overseen the greatest investment in climate change prevention or that he oversaw the strictest regulations with relation to climate change, but these are all implicit claims without adequate clarification or evidence. Moreover, because these claims do not clarify any quantifiable metric that was used to substantiate them, they are closer to value judgements rather than factual claims and definitionally cannot be considered facts, aside from being ambiguous.

Comparing the two debates I found that in the 2024 debate the presidential candidates together produced 59 plausible facts in 1.5 hours, while in 1960 the candidates produced 106 plausible facts in only 1 hour. It follows that Kennedy and Nixon provided almost double the information in ⅔ the time. Moreover, I should add that the information given in 1960 was much more extensive than in 2024, with the former candidates most often presenting information in a logical sequence:

“We find that your wages have gone up five times as much in the Eisenhower administration as they did in the Truman administration… we find that the prices you pay went up five times as much in the Truman administration as they did in the Eisenhower administration… This means that the average family income went up 15% in the Eisenhower years as against 2% in the Truman years.”

By contrast, the current candidates often presented their facts in a manner which introduced prolonged tangents about the severity or extremity of a topic without using any supporting facts:

“We have an Article 5 agreement: an attack on one is an attack on all. If you want to start the nuclear war he keeps talking about, go ahead. Let Putin go in and control Ukraine and then move on to Poland and to other places. See what happens then. He has no idea what he’s talking about.”

Hard statistics, however, were comparable between the two debates, with 22 statistics used in 2024 compared to 29 statistics used in 1960. The surplus of non-statistical plausible facts in 1960 was likely because most of the facts given by Kennedy and Nixon were explanatory and used to describe specific events or programs. Biden and Trump did not elaborate in this manner, but instead used statistics disjointedly and otherwise spoke assertively without much explanation.

The second major difference between the two debates was the type of language used by the candidates. In 2024, language that expressed extremes – the minimum or the maximum – was much more prevalent than in 1960. For example, the words “best” and “greatest” together were used 12 times in 2024 as against 0 times in 1960; the phrase “in history” was used 19 times in 2024 as against 1 time in 1960; the words “most” and “highest” together were used 15 times in 2024 as against 2 times in 1960; the word “ever” was used 23 times in 2024 as against 0 times in 1960; and the word “worst” was used 13 times in 2024 as against 0 times in 1960. The tendency of contemporary candidates to hyperbolize is obvious, as the word destroy was used 14 times in 2024 as against 0 times in 1960. While much of the language can be attributed to Donald Trump’s style, it was certainly not one-sided as Joe Biden had a fair share of these words and used them almost as frequently in his responses. Not even the Cold War rhetoric of 1960 was as flamboyant as how modern candidates speak about domestic issues, showing that contemporary elections place a premium on expression at the expense of information.

A third and most obvious difference was the number of accusations/insults used by the candidates in the 2024 debate. In 1960, there was only one accusation, which was given by John F. Kennedy:

“One party is ready to move on these programs and the other party gives them lip service.”

By contrast, in 2024 there was a total of 81 insults/accusations given by the candidates towards one another, including severe personal insults:

“He’s become like a Palestinian, but they don’t like him because he’s a very bad Palestinian: he’s a weak one.”

These also included accusations and claims about the other candidate:

“He should be in Jail [...] It’s been a terrible thing, what you’ve done [...] I’ve never heard so much malarkey in my entire life.”

“You oughta be ashamed of yourself: What you’ve done, how you’ve destroyed the lives of so many people.”

In total, the candidates gave 22 more insults/accusations than they did plausible facts. This comes in stark contrast to the debate of 1960 in which the candidates together made mutually reinforcing remarks five times:

“Senator Kennedy has suggested in his speeches that we lack compassion for the poor and for others that are unfortunate. Let us understand throughout this campaign that his motives and mine are sincere… I know Senator Kennedy feels as deeply about these problems as I do. But our disagreement is not about the goals for America, but only about the means to reach those goals.”

“I think the question before the American people is: as they look at this country and as they look at the world around them, the goals are the same to all Americans; the means are a question… If you feel that everything that is being done now is satisfactory… then I agree; I think you should vote for Mr. Nixon.”

A fourth contrast is the low emphasis on giving thorough policy descriptions in the most recent debate. I consider an adequate policy description to be one in which a candidate gives sufficient information as to how the policy will work. For example,

“I therefore suggest that in those basic commodities which are supported that the federal government after endorsement by the farmers in that commodity attempt to bring supply and demand into balance; attempt effective production controls.”

I found that there were 11 adequate policy descriptions in the 1-hour 1960 presidential debate while there were only 4 adequate policy descriptions in the 1.5-hour 2024 debate. This demonstrates a clear shift in focus away from explanation about how policies function and a substitution of this information with other talking points. It is also important to note that the large number of non-statistical plausible facts used in the 1960 election could be accounted for by the amount of time giving thorough policy descriptions. In the most recent debate, the time was filled with opinionated responses and frequent insults and accusations.

Evaluation

Graph of perceived debate performance between Biden and Trump in 2024 according to FiveThirtyEight.

It appears, then, that only one of the debates was genuinely informative while the other relied on pantomimes. However, much of the rhetoric was antithetical, that is, the candidates spent large amounts of time slandering each other rather than trying to convince voters of their own policies. Moreover, this sort of behavior seems to be the product of an audience which cares more about how expressive the candidates are than about the plausibility of their arguments. In the recent debate, Joe Biden gave 43 plausible facts to Trump’s 16 and gave all 4 adequate policy descriptions. Meanwhile, Trump gave more insults by a fair margin and used more extreme language than Biden. However, most viewers feel that Donald Trump won the debate despite his lack of substance. Ten out of twelve New York Times columnists claimed that Trump won the debate, with Dan McCarthy writing “Trump won as the more commanding presence,” and Kristen Anderson writing “True debate on substance was rendered nearly impossible”. According to ABC News, 60.1% of voters felt that Trump won the debate, while most were off-put by Biden’s “hoarse and stumbling delivery”.

Conclusion

It follows that voters care more about delivery and assertiveness in political debates than they do about information and plausibility, which is selecting for candidates who rely more on pantomimes than factual arguments. As a result, politicians lack incentive to educate their supporters because of their disinterest in being informed, which instead endorses a polarized and brutish politics. This highlights the necessity for more research as to how and why voter activity contributes to political behavior generally and polarization specifically, and whether there is a similar cause between the modern political climate and that of the McCarthy era. I suggest that voter behavior may itself pose a serious threat to American democracy.