Contextualizing the Modern Captagon Trade

Written by Justin Feldman and Ethan Garcia; Edited by Alex Tapia and Anika Kanitkar

Published on April 15th, 2025

This is the first in a multi-part series exploring Captagon and the future of the amphetamine trade inside the Middle East. In this article, we contextualize the importance of Captagon and explore its associated trade to both the former Assad regime and various non-state actors within the Middle East.

Understanding Captagon

On October 7th, 2024, Hamas fighters from the Gaza Strip initiated an attack on Israeli soil. This attack caused the deaths of approximately 1,300 Israeli citizens and the abduction of about 240 Israeli citizens. According to the United States Intelligence Community’s analysis, the soldiers participating in the attack had Captagon pills on their person. Shortly after the attack, in a statement with regard to efforts to pass legislation punishing those involved in the Captagon trade, Congressman Jared Moskowitz stated: “I was horrified to learn that Captagon pills were found on the bodies of dead Hamas terrorists, allowing them to remain alert and restless as they slaughtered innocent men, women, and babies.”

Fenethylline, otherwise known as Captagon, is a cheaply produced stimulant that reportedly functions as a central nervous system (CNS) excitant. It produces effects that are more intense and prolonged compared to its primary metabolite, Amphetamine. Rising demand for the drug since the early 2000s caused a synthetic restructuring of the pill, in which the active compounds were modified in a key reformulation of the drug in order for the production to expand at scale. Now, almost all modern Captagon pills no longer contain any fenethylline. Instead, any tan or yellow general amphetamine is marketed and sold under the name of Captagon, regardless of the chemical compounds contained within the pill. Captagon’s name previously made reference to a specific, brand-name chemical compound and has evolved to become a catch-all for cheap amphetamines sold within the Middle East.

The main differences between Captagon and other amphetamines (such as crystal methamphetamine) are their intended use, danger, and addictiveness. Generally, Captagon is a “high usage low fatality” drug, meaning there exists wide usage without high fatality rates from those users, which differs from other amphetamines such as crystal methamphetamine, which are “low usage, high fatality.” This provides Captagon with an important marketing advantage over “harder” amphetamines since the general perception of the drug is closer to “soft” stimulants such as Adderall and Ritalin. This is important considering that Captagon was historically prescribed as a Depression/ADHD cure and is thus generally seen to be preferred by the population to other, harder drugs.

Captagon is often consumed recreationally, but it has gained infamy for abuse within militant groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and Hamas. For instance, preliminary reports from the 2015 Paris attacks indicated that “Captagon might also have been used by the incriminated Islamic State fighters.” This is not only because of Captagon’s ability to keep militants awake and alert during attacks but also because of Captagon’s supposed propensity to “make you go to battle not caring if you live or die.”

According to the American Drug Enforcement Agency, Captagon has been one of the major drugs of choice for individuals living within the Middle East, specifically in the Gulf states, since as early as 1981. However, in recent years, as the production of the drug has shifted away from the broader region and has become centralized inside Syria, the drug's impact on the region has dramatically evolved.

Captagon and the Assad Regime

Until the fall of the Assad regime in December of 2024, the production, distribution, and consumption of Captagon played a central role in maintaining the power of both major autocracies and non-state militancy groups. Alongside illicit financial transfers and the extraction of natural resources, the industrial-level production of Captagon allowed the Assad regime to fund itself while isolated from the international community due to extensive sanctions. Hezbollah’s profits from operating its trade funded the organization’s political endeavors and military capabilities while enriching its internal leadership.

The Captagon industry has experienced massive shortages moving into 2025 due to the simultaneous fall of the Assad regime and Hezbollah’s leadership and military power. The Assad regime, through Hezbollah's distribution network, had directly controlled 80% of the $25 billion industry. As of January 2025, high stockpiles of the drug from major dealers throughout the Middle East have allowed for relative price stability at around $1-2/pill near Syria or $8-9/pill near the gulf. As spring approaches, the price of the drug is expected to skyrocket. As a result of this shortage, those reliant on Captagon, including anyone from terrorists to college students to taxi drivers, may soon not have access to the drug.

Because of this upcoming shortage, it is extremely important to contextualize the prior importance of Captagon to the survival of both non-state actors and regimes. It is equally important to carefully consider and weigh each potential scenario for what the Middle Eastern stimulant market could look like in the near future. This includes analyzing both the types of drugs that may emerge and the actors likely to produce them over the next 1–5 years. These developments will have significant implications for the balance of power and overall stability of the Middle East.

The potential shortage, compounded by the present power vacuum within the trade, creates an unequivocally lucrative market opportunity. Contextualizing its importance to non-state actors and autocratic regimes is extremely important, as it can help predict how the market will fill in its present gaps. The implications of this market vacuum are immense and diverse, as how it evolves can affect anything from the balance of power to public health to political stability.

Contextualizing Captagon’s Importance

Captagon Consumption and Terrorism

The Islamic State is not believed to be directly participating in the trade of Captagon, but “observers believe that ISIS taxed the movement of Captagon through its territory – rather than being directly engaged in the production and trafficking.” Nonetheless, the Islamic State is known to use the drug as it carries out acts of violence, including the 2015 Paris attacks. There have also been unconfirmed reports that the 2024 ISIS-K attack on Crocus City Hall in Moscow was fueled by Captagon as well.

B Captagon is hard to detect via blood test due to considerable variation in its composition. As such, many of the details about the consumption of Captagon by insurgent fighters are unknown. However, investigations suggest a significant amount of these fighters do take the drug before battle. According to transcripts of conversations with fighters who use the drug, it is often consumed to boost one’s sense of power and self-worth, as well as to increase alertness and reduce caution. This creates a dangerous blend of overconfidence and lack of fear. While this does not directly lead to an increase in violence, individuals seeking to carry out a terror attack may use Captagon in order to mentally enhance their ability to commit atrocities.

Although the use of hard drugs, such as amphetamines, counter Quranic law regarding altering one’s state of mind, Captagon’s use has become a social ritual within terrorist groups. It serves to promote camaraderie through action against those opposed to Islamic ideology and, more broadly, as a means of antagonizing the Western world as a whole. Much like how the Syrian state and Hezbollah have grown dependent on the substance for maintaining political power, the IS and Hamas have increasingly used Captagon to maintain the degree of brutality in their campaigns and the credibility of their threat to the West.

Captagon Production and the Assad Regime (Pre-December 2024)

The Syrian government finances itself through Captagon to make up for its exclusion from international trade. Beyond the sanctions, the civil war triggered a significant decrease in imports and exports, an increase in capital flight away from the country, a 45% drop in oil production, a noticeable decrease in public revenues, an increase in unemployment to 55%, and a decrease in nominal GDP from $252.5 billion in 2010 to $16.47 billion in 2015. Regardless, political scientists Zaki Mehchy and Rim Turkmani attribute the sale of Captagon to the sanctions: “The sanctions have contributed to the flourishing of illegal activities conducted by the cronies and warlords in coordination with criminal networks inside and outside Syria.” This underscores the greater idea that, in general, without Captagon and other illicit income sources, the Syrian government would have otherwise collapsed due to these sanctions.

The production of Captagon has become critically important to the Assad regime, particularly as a means of supplementing the country's income. In recent years, Syria’s place in the Captagon trade has changed from being a transit country to becoming a producer country. This shift is partially explained by the fact that many key members of the Assad regime developed financial investments in the Captagon trade early in the war and relied on its income to fund the war effort.

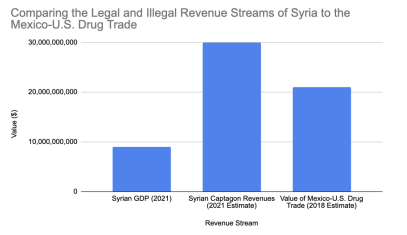

Comparison of Legal and Illicit Revenue Streams of Syria to the Mexico-U.S. Drug Trade

The Syrian government was able to quickly take control over the production of the drug because it had what many non-state actors such as Hezbollah did not: internationally recognized sovereignty within their territories and pre-existing, exploitable infrastructure, such as industrial buildings, running water, electricity, and proper roads. Syria was able to rationalize the importation of massive quantities of both amphetamine, theophylline, and other filler drugs to the international community by establishing fake pharmaceutical companies. Because the Syrian government was able to produce the drug at scale and without the concern of drug busts, the Assad regime was also able to considerably reduce the price per unit of Captagon to as little as $3 per pill. The leading trafficker of the drug internally within Syria is the Syrian Fourth Division, a part of the Syrian military run directly by Bashar Al-Assad’s youngest brother, Maher Al-Assad, allowing it to be effectively trafficked across the country without fear of international seizure. This division is also known as the Fourth Armored Brigade.

Before the fall of the Assad regime, Syria’s industrial-scale production of Captagon propelled it to become the primary source of Captagon for the entire world. Syrian Captagon exports at one point accounted for over 80% of all Syrian foreign exchange receipts. The annual estimation for illicit Syrian Captagon exports in the year 2023 is valued at $30 billion. For comparison, the estimated value of the Mexico-US drug trade, considered one of the most profitable drug trade systems in the world, was around $21 billion as of 2018. This valuation is more than three times Syria’s official GDP, which stands at $8.97 billion. Out of the total value of these exports, the Assad regime had been estimated to profit around $6 billion per annum directly from Captagon, revealing the extent to which the Captagon trade empowered Syria’s autocracy. Captagon was a direct contributor to Syria’s success in retaining power during the civil war, providing a revenue stream for weapons purchases, which made it nearly as important to the survival of the Assad regime as his foreign relationships.

A Captagon Production Facility Inside an Assad-Regime Mansion

The fall of the Assad regime has offered unparalleled insights into the mechanics of Captagon production operations within the state. Three major production facilities have been discovered in Homs, Latakia, and Darra. Various smaller labs have also been discovered throughout the country, a large portion of which were within the personal homes of those connected to major Assad allies. These allies often included members of the aforementioned fourth armored brigade, providing further support to the thesis that the profits from the trade were heavily intertwined with the ability of the Assad regime to finance itself. These recent findings confirmed previous estimates of the size and sophistication of the production and distribution network and helped illustrate the extent to which Captagon served as the crucial means of survival of the Syrian state from both a militaristic and economic standpoint.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the organization that has become the main governmental party of Syria, has forecasted major crackdowns on everything having to do with the production and consumption of Captagon within the country's borders. The organization has long led seizure efforts even before its rapid rise to power and has shown a great degree of capacity in accomplishing such efforts in recent months. Though there are concerns that the regime may become too overwhelmed to follow through on such efforts, it is likely that the country will cease to be a major player in the production of Captagon in years to come.

Captagon Production and Hezbollah (Pre-December 2024)

While the Syrian state is considered the primary producer of Captagon, there must be a robust distribution network that connects the Syrian-produced goods to the wider Middle East. This is especially important considering the main and most high revenue consumers of the drug are based outside Syria and largely in the Gulf states. Hezbollah, in cooperation with the Syrian state, spearheaded distribution throughout the Middle East before their control over the Beirut airport was dismantled by an Israeli military campaign in 2024.

Quranic teachings forbid the usage of stimulants. Instead, terrorist groups distribute Captagon with the belief that their ends, their struggle against the West, as a manifestation of the principle of jihad, overshadow their means or participation in the drug trade. To this end, it serves a strategic purpose: it harms the enemy Western society, or more aptly, other societies influenced by and aligned with the West, by weakening their resilience to a crisis of drug addiction.

Therefore, when considering the rationale for why traditionally Islamic fighters opposed to the consumption of these drugs are the same ones trafficking it, the key conclusion to what is the primary appeal of selling Captagon lies not in its ritual use as much as in how it is one of the only ways, given sanctions and lack of export industries, to make cash in a quick fashion. This is because there are very low barriers to entry in this market, since the precursor materials for the drug can be found everywhere, from drug stores to broom closets. The manufacturing infrastructure often involves household products, ensuring that purchases of equipment aren’t easily detectable. The returns are especially high, given the financial profitability of the drug.

Map of Key Captagon Smuggling Organizations in the Middle East (Pre-Dec, 2025)

Hezbollah’s success in monopolizing the Captagon’s distribution can be attributed to a few factors. First, it established an “international operational infrastructure” via the wider Lebanese, Iranian, Iraqi, and Palestinian Shi’ite emigrant communities around the world. This allowed the organization to connect buyers and sellers efficiently. In addition to ethnic ties, Hezbollah shares an allegiance to the Iranian Ayatollah with groups such as Islamic Jihad, Hamas, and the Houthis. This connection also contributes to the strength of its global trade network, as through these connections, peer-to-peer distribution is able to become more streamlined, and dealers between the two agents are deemed to be more trustworthy. Therefore, as long as Syria was able to traffic the drugs into the hands of Hezbollah fighters, distribution through these pre-existing networks had become relatively simple.

Additionally, Hezbollah maintained a high degree of decentralization, making it impossible for governments to bring down their trading network despite an otherwise effective and organized structure. Hezbollah has also consistently shown a willingness to work with external drug dealers and pre-existing drug networks in order to meet its goals. For example, the organization had long been linked to Merhi al-Ramthan, a prominent Syrian drug kingpin killed in a May 2023 Jordanian airstrike who had close ties to Bashar al-Assad.

The success of this network is also dependent on the unique relationships between Iran, Hezbollah, and Syria. Iran, as the state most directly responsible for funding Hezbollah, is a key ally of Syria. In August of 2023, Vahid Jalalzadeh, the head of Iran's parliamentary national security and foreign policy commission, stated: “Just as we have been with the Syrian government and people in the war with terrorists, we will also be with them in the economic war.” The trade is aligned with Iran’s geopolitical goals and is even indirectly supported by the regime despite the country's extremely harsh anti-drug laws.

The rationale for cooperation between the Shi’ite theocracy and Alawite autocracy is twofold. The countries have primarily worked together to counteract pressures from the international community, as well as from Sunni movements dating back to Iran’s assistance of Syria in the Iraqi invasion of the country. Assad also views Hezbollah, a proxy of Iran, not only as an important buffer between Israel and Syria but also as a vector for his country's interests within Lebanon. Therefore, the relationship between Iran, Syria, and Hezbollah can be described as “a reciprocal, symbiotic relationship between Iran and Syria [which] demands Iranian support to the Assad regime, and in turn demands Hezbollah’s support to the Assad regime.”

Hezbollah, while not as entirely reliant on the Captagon market as the Assad regime, still benefits from its role in the trade. As Syrian investigative journalist Taim Alhajj Hazza stated, “the Hashish and Captagon trade is one of the most important sources of funding for Hizbullah under the direction of Iran.” Captagon’s profits, while not the only source of funding for the organization, provide Hezbollah with a significant portion of its military network and political campaign funding within Lebanon. While it would be disingenuous to consider their rise to power within Lebanese politics as a consequence of their role in the Captagon trade, their increasing establishment in electoral politics since 1992 has necessitated more consistent funds. This financial necessity has, in part, incentivized Hezbollah’s entrenchment in illicit economies that are difficult to trace and can operate with a degree of plausible deniability. Captagon, with its lucrative margins and demand across the Gulf, offers a relatively low-risk, high-reward mechanism for revenue generation. Moreover, Hezbollah’s involvement in the trade reinforces its utility to both Iran and Syria: to Iran, as a regional actor capable of projecting power and influence through asymmetric means; and to Syria, as a stabilizing force that can help secure key trafficking routes, especially those connecting Syrian manufacturing hubs to Lebanese ports. The convergence of political, military, and financial imperatives has, therefore, turned Hezbollah into a logistical linchpin within a broader narco-political alliance—one that not only sustains the Assad regime but also anchors Iran’s regional strategy through transnational illicit networks.

Highly circulated IDF image showcasing the elimination of Hezbollah Leadership (August, 2024)

What is perhaps even more important is their aforementioned relationship with Syria and other Iranian proxies that rely on Captagon to maintain their morale. Through their relationship with Syria, members of Hezbollah have a greater degree of freedom and protection within the borders of the country. Additionally, through their relationship with the thousands of proxy forces that receive the drug directly from the organization, Hezbollah reaps influence and cultivates loyalty from these terrorists.

Hezbollah, through its connections with Syria and the Captagon trade, has been able to turn itself into what has been described as a ‘state within a state. ’ It maintained a presence in the Lebanese parliament and government while also operating its own political, military, and social services network with a great degree of impunity. Furthermore, through Captagon, Hezbollah has made major alliances outside Lebanon, such as with the variety of terrorist organizations and Syria. , which has led to Hezbollah becoming reliant on the Captagon market in order to continue growing its influence and its military capabilities.

Following the vast and sophisticated Israeli attacks against Hezbollah leadership in late 2024, the status of Hezbollah as a major actor within Lebanon has been called into question. After these widely successful attacks, nearly every major member of Hezbollah leadership within the country has been killed, and a major portion of their weapon depositories have been destroyed. The diminished status of Hezbollah in the present (January 2025) compared to this time last year can be best exemplified by the Lebanese parliamentary elections. Joseph Aoun, a Maronite general who ran on a platform of the disarmament of Hezbollah, was elected despite the terrorist group publicly coming out against the candidate.

It has also been reported that since the war with Israel, the organization has lost control over both the Beirut Airport and Seaport, both of which used to be two of the major transit hubs for Captagon. Foreign governments are beginning to acknowledge that Lebanon’s role as a key actor in the trade is to denigrate over time. Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister announced a visit to Lebanon after strained relations due to the Captagon trade, indicating the expectations of foreign policy changes.

Photo of the aftermath of an IDF airstrike against a Hezbollah weapons depot (July, 2024)

Lebanon’s specific role within the Captagon trade means that these developments are particularly straining. Beyond being the origin of nearly a fifth of Captagon within the region, Lebanon’s primary status within the trade is as a transit hub and a safe intermediary between major players in the Captagon trade. For example, the US Treasury OIA identified Lebanon-based Khaldoun Hamieh as an integral member of the financial network surrounding Captagon. He has traded weapons and armored vehicles for the Syrian military and has also donated over $1M to Hezbollah, all to secure safe passage for Captagon. His associates have lent their business names to conceal the financial network present within Lebanon that serves as the infrastructure for the operation of Hezbollah. These routes have presumably been cut off by recent developments in Syria and Lebanon and are being more extensively monitored by foreign intelligence and domestic drug enforcement. Thus, Lebanon’s role is expected to diminish significantly.

Conclusion

Once Captagon is properly contextualized within the backdrop of the Middle East, the production and trade of this drug exemplify the importance it plays in the economic and political survival of regimes and non-state actors alike. In the case of both Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Assad Regime in Syria, Captagon had a major impact on both groups' continued success in the 2010s and early 2020s. However, with the fall of the Assad regime and Hezbollah's diminished capacity stemming from their war with Israel, the trade faces a critical transformation. As spring approaches, reserves of the drug are bound to decrease rapidly, which will lead to a massive shortage of amphetamines in the region with a massive market reliant on the drugs.

Because of this eventual massive gap in the market between supply and demand, it is inevitable that either the drug industry in the Middle East will shift to the consumption of different drugs or new actors will rise up to produce and distribute Captagon. Either way, whoever seizes this opportunity will be of immense and immediate consequence to both the balance of power and stability of the Middle East.

In order for policymakers in both the United States and abroad to seize this opportunity, the best one America and her allies have had in decades, to stop the next narco-state from rising, it is imperative that three main aspects of the future drug trade are fully understood: potential producers of Captagon, potential alternatives to Captagon, and the potential transit routes that will be formed in this new era of drug trafficking within the region. By fully understanding the probability and impacts that these three factors will play, it is possible that the United States can limit the production of amphetamines to comparably smaller and less politically important actors.